An Introduction to Elm for React Developers

Elm is probably my favourite programming language - its opinionated but welcoming design provides a compelling case study in how language design can gently guide developers towards writing maintainable code.

Why would a React developer learn Elm?

Elm is a language designed for creating frontend applications, offering an alternative to JavaScript libraries like React. Both were created circa 2012, Elm as an academic thesis project, and React as an industry-backed library. The underlying technology to both is a virtual DOM and a declarative programming style for creating user interfaces. The main difference between the two is that, while React is simply a library built for JavaScript, Elm is an entire domain-specific language, designed from the ground up for purpose.

This means Elm has some language features which are now considered best practice in JavaScript development, such as immutability, lambda functions and type safety. But Elm goes further than React and TypeScript in many ways, with such a powerful type system that it can boast 'No runtime errors in practice', and a significant speed improvement over its competitors.

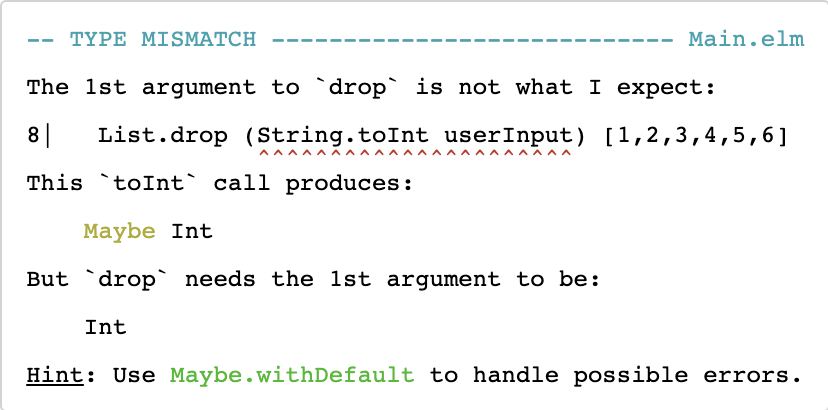

As TypeScript gains more popularity, I wonder which other Elm features will move into React. My personal hope is that the famously friendly error messages (see image below) will make their way into the language. Elm is a compiled language, so the compiler is re-run after code changes to generate JavaScript for the browser. While this seems like a hindrance, I find the development loop quite engaging: a kind of 'type-driven-development' where the compiler helps guide your work, and gives the developer greater confidence in their code. This 'live-recompile' is made possible due to Elm's lightning-fast typechecking and compiling, something TypeScript is still sorely lacking.

The history of programming language adoption shows us that what's popular isn't always best, as the trending languages of today are often successful by pure coincidence - or as a result of corporate marketing campaigns. I truly believe the industry is moving towards functional programming: React's creator, Jordan Walke, said himself that ReasonML (a functional language closely related to Elm) is 'the language of React'. He posits that, after the success of React, we should once again turn to functional programming and ask 'What else did we miss?'

An Example Project

To help developers familiar with React get to grips with the syntax, I've written the same application in Elm and React, a counter with an increment and decrement button (I've excluded a bit of boilerplate code and import statements from both to simplify things). The page looks like this:

JavaScript:

const App = () => {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

const increment = () => setCount(count + 1);

const decrement = () => setCount(count - 1);

return (

<div>

<button onClick={decrement}>-</button>

{count}

<button onClick={increment}>+</button>

</div>

);

};

Elm:

type Msg = Increment | Decrement

init = { count = 0 }

update msg model =

case msg of

Increment -> { model | count = model.count + 1 }

Decrement -> { model | count = model.count - 1 }

view model =

div []

[ button [ onClick Decrement ] [ text "-" ]

, text (String.fromInt model.count)

, button [ onClick Increment ] [ text "+" ]

]

As you can see, the two programs are similar in many ways, and quite different in others. If you're struggling with the somewhat alien ML-style syntax, check out this quick syntax guide.

To start, we define our Msg type to be either an Increment or Decrement value - more on this later.

After that, the Elm program is split across 3 self-contained function definitions, init, update and view. This contrasts with React, where everything is contained within one function.

The init function is much like the 2nd line of our React app: it defines the initial state of the Model, essentially the datatype for the entire application's state. Unlike when we use React's Hooks, we are encouraged to store all the state for our entire application in one data structure, for reasons discussed later.

The update function then takes two arguments, the Model and a Message. It then decides how to change the model based on the message received, returning a new copy of the model with the count changed. You can read the code { model | count = model.count + 1 } as 'a copy of model where its count is one greater'. Elm calls this function for us whenever a new message is sent, for example on a button press.

Finally, the view function then takes one argument, the Model, and renders it as HTML. Other than the style, this is mostly the same as the return statement in the React function - except that in Elm our buttons send Messages rather than call lambdas. Elm calls view to re-render the page whenever the Model changes.

What benefits does this style provide?

Most of these differences are a result of the fact that Elm is a purely functional language, meaning we aren't allowed to perform any 'side effects' as we would in React with Hooks. Functional purity gives us important guarantees about our codebase - we can be sure that, given the same inputs, we will always get the same output. In a practical sense, this makes the code easier to read - you know the only values that will change in a function are its parameters, so you don't have to waste time reading the whole surrounding context. This is one reason why Elm files can be longer than JavaScript ones without compromising maintainability, as the smallest unit you have to comprehend is a function, not an entire module.

However, separating out the code into init, update and view has other benefits - the separation between code describing the application logic and how it looks is now enforced by the language.

The guide refers to this structure as 'The Elm Architecture' (see diagram above). The Elm runtime manages our application for us, calling view whenever the model changes and update with every message received. The interactions here will be familiar to users of Redux, which was inspired by Elm, where a Redux 'Action' roughly approximates an Elm Message, and update is akin to a 'Reducer'.

Having a centralised Msg and Model type can boost productivity, as changing these types in a large module will cause the compiler to alert us to all the places that subsequently need updating, freeing us from the task of searching through the codebase manually. Centralising the state into a single Model also has architectural benefits. It allows us to make illegal states un-representable, and forces us to thoroughly describe all the dynamic aspects of our webpage. Modelling the state of our application as a data structure in this way is a powerful tool, that helps us consider what really lies at the core of our application.

A stricter type system can seem like a limitation, as an example, where React lets us simply write {count}, Elm makes us write text (String.fromInt model.count), converting the Int to a String to Html. However, as TypeScript evangelists will tell you, the advantages of type safety often outweigh the additional work, as it increases the predictability of the code and, in Elm's case, eliminates the possibility of a runtime error.

Where are these famous types?

In Elm, types can usually be inferred from the code you write, so you almost never need to write type annotations to reap the rewards of type safety. However, they are often considered good practice as they can make the code more readable and help the compiler show better error messages. So, for the sake of interest, here is the above program with type annotations:

type Msg = Increment | Decrement

type alias Model = { count : Int }

init : Model

init = { count = 0 }

update : Msg -> Model -> Model

update msg model =

case msg of

Increment -> { model | count = model.count + 1 }

Decrement -> { model | count = model.count - 1 }

view : Model -> Html Msg

view model =

div []

[ button [ onClick Decrement ] [ text "-" ]

, text (String.fromInt model.count)

, button [ onClick Increment ] [ text "+" ]

]

First, we give the Model a formal type. We use the syntax type alias here, because we're not introducing a new set of values (as with Msg), simply a shorthand for { count : Int }, a record with an integer field called 'count'. We use this new type to annotate the declaration of init, saying it is just a constant of type Model.

Next, we give update a type annotation, Msg -> Model -> Model. This is essentially saying 'update is a function which takes a Message and a Model, and returns another Model'. This is somewhat obfuscated by the fact Elm functions are 'curried' by default, making the actual meaning more like 'update is a function which takes a Message, and returns a function which takes a Model and returns a Model'.

Finally, we annotate view with the type Model -> Html Msg. This states that the view function takes a model and returns some HTML, specifically HTML with our custom Messages embedded within it. This is a form of parametrised type: the TypeScript equivalent would be Html<Msg>.

What next?

If you're interested in experimenting with Elm, you can neatly integrate Elm components into your personal React projects using @elm-react/component.

For those interested in learning more about the language and its influence on frontend development, I'd recommend one of my favourite talks, 'The life of a file' by Evan Czaplicki, Elm's creator.

Thanks to the compiler's helpful and friendly error messages, the language almost teaches itself (after a brief skim of the guide) - so if you're a 'learn-by-doing' type of developer I recommend elm-live to re-run the compiler every time you change your file. It's an interesting, even somewhat calming way of programming, and while the language may not have seen mainstream success yet, I think it can continue to show us a glimpse of the future of web development.