Faux-Controlled Components

My team recently spent the best part of two days debugging a React component.

The bug was caused by what I'd describe as a Faux-Controlled Component, and was solved by useMemo-ing one of its props.

It provides a useful case study for people (like myself) who think they understand React, but do not.

Part 1: Equality

Let's take a tour of the most popular programming languages and see how their == operator compares two lists, both containing the number one. (I'm aware critique of JavaScript's equality rules is cliché, but I promise it's relevant).

Go: ✅

xs := [1]int{}

ys := [1]int{}

xs == ys // true

Java: ❌

int[] xs = { 1 };

int[] ys = { 1 };

xs == ys; // false

Python: ✅

> xs = [1]

> ys = [1]

> xs == ys

True

JavaScript: ❌

> let xs = [1]

> let ys = [1]

> xs == ys

false

A lot of disagreement about something quite simple!

While perhaps not as intuitive, I wouldn't say Java and JS are "wrong" here. Is the list on the left 'the same as' the list on the right? They have the same content, but that doesn't really make them the same list. You could change the number in xs, and it wouldn't change in ys. In this way they are two distinct entities.

In fact, if it wasn't for JavaScript's ability to quickly check if two things are exactly 'the same thing', React's fast rendering wouldn't be possible! I'll come back to the importance of this later.

Part 2: Lies I've Told About useMemo

Here is a slide from a training I've given about React Hooks:

useMemo - Don't use it everywhere!

If the operation is cheap, there's no point.

❌ const first = useMemo(() => items[0], [items]); ❌

✅ const first = items[0]; ✅

What's the lie here?

Some operations are cheap, but a useMemo will still have an effect.

In the same way useCallback does, useMemo ensures that, given that the old dependency array 'equals' the new dependency array, we keep the same memory address. This is important if you're passing props down to memo-ized components, to avoid unnecessary re-renders when nothing has changed.

For some expressions, useMemo does not make any difference. Here are some examples of useMemo being applied wrongly, as the memory address would remain the same without it:

// accessing an array index: you always get the same address

const x = useMemo(() => xs[0], [xs]);

// arithmetic: numbers are compared based on their value

const x = useMemo(() => 100 * 100 + 100, []);

// calls that return strings: strings are compared based on their value

const name = useMemo(() => person.getName(), [person]);

For others, useMemo does matter. Here are some examples when useMemo was needed (but forgotten):

// putting something in an array: a new array is created every time

// even though this is a simple operation, unless useMemo'd

// it will return a new object every time!

const xs = [x];

// constructing an object... same as above

const person = { age: 101 };

So how could I fix the slide? We need to add another condition:

useMemo - Don't use it everywhere!

If the operation is:

- cheap

- AND returns the same address every time

There's no point.

❌ const first = useMemo(() => items[0], [items]); ❌

✅ const first = items[0]; ✅

Most misuses of useMemo go unnoticed, and most of the time, misusing it doesn't matter much. Why? Re-renders in React are usually cheap, and won't cause a real re-render in the DOM unless something actually changed.

It's almost not worth the developer's time to apply useMemo correctly - a pretty dangerous notion, as mistakes can be very hard to fix.

Part 3: Je Déteste Faux-Controlled Components

The React documentation defines 'Uncontrolled Components' as components controlled by data in the DOM, not a React Component. It's conventional wisdom that they should be avoided at all costs.

However, the 'Controlled/Uncontrolled Binary' isn't quite as black and white as this definition implies. When you're using components you've downloaded from npm, you might stumble upon a 'Faux-Controlled Component'. 'Faux-Controlled Components' are React Components which, while their state is not stored in the DOM, hides state from the developer & keep the issues of Uncontrolled Components as a result.

An example of a 'Faux-Controlled Component' is react-date-range's DateRange. Looking at the docs, things don't seem too bad:

const App = () => {

const [ranges, onChange] = useState(/*...*/);

return (

<div>

<DateRange onChange={onChange} ranges={ranges} />

</div>

);

};

The DateRange is controlled! The user can pass down state and a callback, giving us complete control of the component. Before you can say 'yarn add' I've made react-date-range (and its dependencies) a part of my website forever.

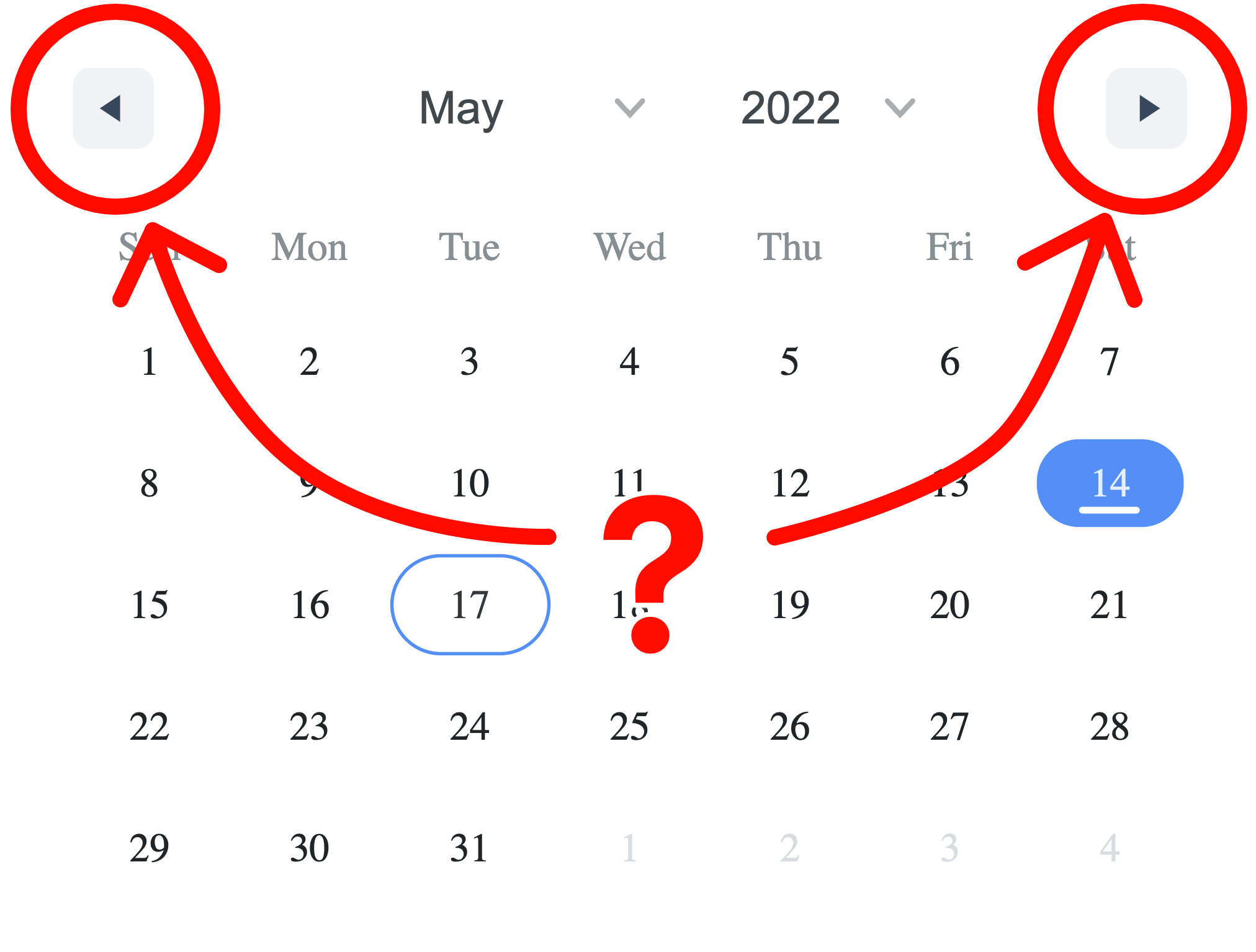

But was I too hasty? What about these month arrows?

These buttons flip the DateRange from one month to the next... The DateRange clearly has some more state than just 'date'. It's not nearly as Controlled as I first thought!

What happens if I want those 'shown date' buttons to behave in any other way?

I could want my DateRange to:

- Only allow the user to view dates in the future

- Move forward 2 months at a time

- Click a button outside the DateRange to advance it

- Perform an action, such as a network request, whenever the user changes month

The library attempts to provide a fix for the first shortcoming: minDate and maxDate props. In fact, the component has over 40 props, almost all of which are optional. Most of them provide a way to slightly change the behaviour of the component.

Why not let me use my own state, and have shownDate and onShownDateChange props? Well, we almost do! Except the docs describe shownDate as the "initial focused date". Unfortunately, it only controls which value the internal state is initialised to. This is a Faux-Controlled Prop!

It's hard to tell why DateRange was designed this way. I would consider this bad API design, but perhaps it's a good fit for the audience. Faux-Controlled Components can be a handy tool for lazy developers who don't want to think about the complexity they are introducing to their application. They'd rather the library handled all this state for them, to save them 'wiring up' 5 or 6 different state values & callbacks when they include complex components.

This is a cowardly attitude. We should meet this complexity head on - if you're adding state to your application, you must consider its implications. Don't let library authors hide it from you. Library authors compete in the npm market - whichever library's front-page code snippet looks simplest will undoubtedly win the most downloads. But what is this faux-simplicity hiding?

Part 4: Betrayal

So what? Maybe Faux-Controlled Components are less customizable. Big deal - 99% of developers just want a DateRange that 'does what it says on the tin'.

This is where Faux-Controlled Components reveal their true problem: unless you treat them with extreme care, they will betray you.

Returning to our case study, I needed to grey out unavailable dates. As the user advanced through the calendar, I had to ask the backend which dates were available in the month they have on screen. While I can't directly know the Calendar's shownMonth, I can use onShownDateChange and my own state to keep track of the month shown. This isn't ideal, but it's enough for now.

I add my callback to onShownDateChange, and suddenly my DateRange is stuck - the Next button doesn't do anything!

A minimal example demonstrating this bug is shown below (also on CodePen):

const range = {

startDate: new Date(),

endDate: new Date()

};

const App = () => {

return (

<DateRange

onShownDateChange={/* setState & re-render */}

ranges={[range]}

/>

);

};

There are two important things to note about this code:

onShownDateChangecauses a re-render, as it calls a ReactsetStatefunction.rangesis set to a new array every time. As discussed in Part 1, creating an array literal outside of auseMemowill make a new object (with a distinct memory address) every single time the code is run.DateRangeis a Faux-Controlled Component

These 3 properties come together to create a perfect storm, and the Next button on the DateRange stops working.

Why?

- We press Next

- So

onShownDateChangeis called - So

setStateis called - So

Appis re-rendered - So

[range]gets a new memory address, even though its value is the same - So

DateRangeshows this 'new' (but not really new) range - ... Sending us back to the initial month

Sending the user back to the original month gives the illusion that the Next button does not work. Why are we sent back to the original month? Whenever ranges is set to a 'new' value, DateRange decides to show that month. We let it manage its own shownMonth state, and this is what it has decided to do with it. If we controlled the shownMonth state, this wouldn't be an issue.

To fix this, we can wrap [range] in a useMemo.

const range = {

startDate: new Date(),

endDate: new Date()

};

const App = () => {

const ranges = useMemo(() => [range], [range]);

return (

<DateRange

onShownDateChange={/* setState (rerender) */}

ranges={ranges}

/>

);

};

Now, we can break the chain of events:

- We press Next

- So

onShownDateChangeis called - So

setStateis called - So

Appis re-rendered - The useMemo makes sure

rangeskeeps the same memory address, asrangeis the same

Not exactly elegant, but at least it works!

Conclusion

How can we prevent this from happening? We must avoid using (& publishing) Faux-Controlled Components at all costs!

Unfortunately React programmers love to hide state - they even call it 'Component Driven' design and act like it's a good idea. Of course, it's not without merit - allowing devs to drop cute little components into their app without having to 'wire them up' with state is an appealing concept, and most of the time it seems to work without any hiccups.

The sad reality is that hiding state inside components is React's biggest strength, and also its biggest weakness. Most of the nasty bugs and design problems I see in React applications stem from this ability. If state is hidden in the corners of your application, distributed across hundreds of tiny components, what hope do you have of keeping your sanity when transitioning the application from one state to the other?

In this sense, React's main competitor is the frontend language Elm. Looking at Elm's design offers us some insight here, as Elm forbids storing state anywhere but the top level of your app (think about it like Redux-only architecture).

This design shows us the downside of prohibiting 'state-hiding' - anyone who has written even a small app in Elm knows the amount of 'wiring', passing values between parent and child components, can be exhausting. As a famous man once said: "While the State exists, there can be no freedom. When there is freedom there will be no State."